Confucius Institute, NO! Confucius, YES!

|

Author: Gang Xu

Date of Original Release: 2018-12-03 06:03:51 Site of Original Release: http://blog.wenxuecity.com/myblog/69325/201812/1989.html |

| |||||||||||||||||||

Confucius and Confucianism is just one of those many great things that, once of interest to China (CCP), would be fully exploited, maximally twisted, and, in the end, fundamentally ruined. Another illustration is the United Nations Human Rights Council, from which the U.S. had to withdraw in June. An ongoing target is America’s rule of law, which has already become a cheap joke to many wealthy Chinese.

While Confucianism is touted only as an ideology on paper in the real world of current China or tailored as a cloak for Chinese government to flex its influence worldwide, many of what it has been promoting are the daily practices in America. As a set of social values that aim at community harmony and long-term social well-being, Confucianism aligns well with American values.

While Confucianism is touted only as an ideology on paper in the real world of current China or tailored as a cloak for Chinese government to flex its influence worldwide, many of what it has been promoting are the daily practices in America. As a set of social values that aim at community harmony and long-term social well-being, Confucianism aligns well with American values.

|

NOTE: In this essay the word Confucianism is used to refer to the traditional core values that have evolved from Confucius’s original teachings, not the propaganda taught and marketed in China today.

On Confucius and Confucianism, I have something unique to share.

I spent most of my primary school years and all my secondary school time in Quzhou (衢州), a city in the western Zhenjiang Province, China. Historically the city used to be the transportation hub of four neighboring provinces and is so named, in Chinese, for its reach to every destination. Two things made my life there a very transforming experience: the Temple of Confucius and my secondary school Quzhou No.1 Secondary School. Quzhou Temple of Confucius and giant ginkgo trees in its yard

To people meticulously knowledgeable about Confucius and Confucianism, Quzhou holds a special and uncontestable place. In 1128, the second year after the Song Dynasty retreated to Zhejiang Province and declared its new capital in current Hangzhou City, following its defeat by the Jin army and loss of its control over China north of the Yangtze River (including Confucius’ hometown Qufu), the 48th-generation eldest grandson of Confucius moved to Quzhou. In Chinese culture the eldest sons are the orthodox descendants when a family tree is examined from a particular ancestor. The relocation to Quzhou of Confucius’s orthodox descendants, who had been serving as the official embodiment of Chinese civilization over much of Chinese history, established Quzhou as a sacred place for Confucianism. A hundred and twenty-five years later in 1253, Confucius’ descendants in Quzhou started to build a Temple of Confucius, a replica of the original temple in their hometown Qufu, apparently out of the hopelessness that they would never be able to return to their home place. (In 1279, Song Dynasty was replaced by Mongol-ruled Yuan Dynasty.) In 1520, Quzhou Temple of Confucius was relocated to its current site and had since functioned as a center for cultural events and education.

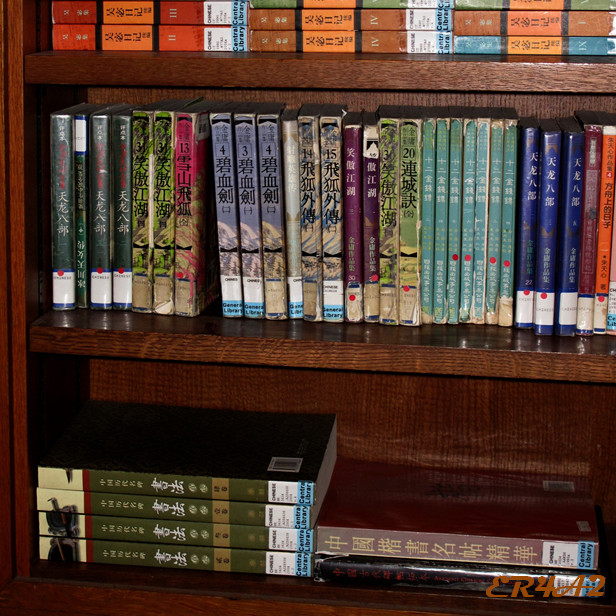

Although Quzhou Temple of Confucius is a local landmark, I had visited the Temple only once before college, in an ironical context and for a ridiculous purpose. When I was attending primary school, China was in a period known as the Cultural Revolution. Confucius and Confucianism, among other traditional Chinese heritages, were the targets of ideological purge. However I had a group tour to the Temple one day, organized by my primary school, to visit the exhibition of “Rent Collection Courtyard” that was hosted in the two side aisles of the Temple. The exhibition was a clay sculpture show that portrayed the devilish nature of a landlord and the miserable lives of farmers working on his land, of course, before the communists took over the China. The whole visit was quite an eerie experience. As I reached the far end of the gallery, I stopped in front of an ancient house, which was towering over loftily on an elevated platform of weathered rock slates. One pupil whispered to me in awe: the house kept the most precious treasure of the Temple, a wood carving of Confucius and his wife; the work was crafted by one of his disciples and passed only along the orthodox descendants of Confucius; it was a well-guarded national treasure. Because we were forbidden to explore the Temple in our visit there for the exhibition, I did not venture to get a closer feel of the sacred house, Dacheng Hall or the Hall of Great Accomplishment as I learned later. A decade later, I also learned that the wood carving was not supposed to be kept in Dacheng Hall and the treasure was actually surrendered to Confucius’s Temple in his hometown Qufu under the directive of the government. Anyway, it was just a talk between two boys. The visit stirred my curiosity about the Temple of Confucius. Yet it was not open to public then; its heavy door was closed almost all the time. One day I passed by the Temple and accidentally looked up into the canopy of a giant ginkgo tree, I become electrified: the tree defiantly announced its endurance in the Temple; over its top, ginkgo fruits scattered over against the blue sky, as shining as red gem stones, beaming, twinkling and inviting. I had never seen a ginkgo fruit that red that translucent! In 1977 I advanced to Quzhou No.1 Secondary School, a school whose origin could be traced to 1788. The School had been the best school in the region; it was one of the nine key secondary schools in the Province when the Communists took power and produced its first list of best schools in 1953. For its prestige, the school during the Cultural Revolution was targeted as an exemplar of all the evil in the old education system, unacceptable in a communist new China; many of its experienced teachers were cleansed. At the conclusion of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, the school was hurt badly and ill-prepared for resumption of its glorious past. It failed to produce a single college admission for three consecutive years. The slipping came to a halt when Mr. Zishan Zhu came to take on the principal position. We became his first graduation class and, thanks to his leadership and all the hard work of our teachers, my class produced a shining college matriculation list and the school recouped its lost title as a key secondary school in the Province, a recognition that was officially accredited by the Department of Education. That was the year 1982. Paradoxically, in retrospect, I actually benefited from the easy load of school work in my first three years there. After the Cultural Revolution, those once-banned works of Chinese literature and world literature started to flood book stores. I read broadly and voraciously. My favorites were classic Chinese poetry and prose. In the summer before college, I became addicted to Chinese martial arts fictions written by Louis Cha. A year earlier, I had learned that Louis Cha was also a graduate of my secondary school. I had heard the story that Mr. Zishan Zhu was so joyful when he dug out Louis Cha’s enrollment card, forty years old, soon after he took office. Chinese martial arts fictions by Louis Cha in Boston Public Library

Louis Cha is probably the most read Chinese author in the world. I always feel related to when the settings of his fictions are examined. First, his stories never seem to happen before Song Dynasty and his most popular fictions involve the history when Song Dynasty battled with the Jin and Liao armies, the period that has a profound impact on Zhejiang Province as a whole and on Quzhou City in particular. Second, although his stories take place often in exotic terrains and proverbial mountains, many scenes in his descriptions appear so familiar to me. Given that Louis Cha grew up in Hangzhou Plain where the geography is rarely that aberrant and arresting, I once presumed that many of his stories were actually set at Quzhou. Indeed Louis later acknowledged that he used Quzhou as the background for some of his stories. Well, not just some, if you had ever walked along the rock-fortified high steep bank of the Quzhou River outside the Great West Gate before 1990’s, watched the Sun setting into that faint ridge beyond a vast expansion of the wild beach across a river that gurgled one hundred feet right below, and then seen, when you turned to leave, a single tiny flower of wild mum squeezing out between two eroded heavy bricks of the old city wall, flickering in the evening breeze and autumn twilight, trying to relate a story of the past. What is truly relevant, which I had never bothered to reflect on when I was young, however, is the values that his fictions had instilled in me. Cha’s works are steeped with Confucianism, echoing so well with the classic Chinese poetry and prose. I felt so comfortable with his stories while being enchanted in his literary narrations. I breathed Confucianism, just like many other Chinese, just like we breathe the air, even though most of the time most of us are not consciously aware of the element that we have breathed in, not cognizant of the oxygen molecule and its formula when our lungs exercise their functions. Then I spent the next two decades studying and working as a scientist, of which a majority in America. Confucius and Confucianism were only a subconscious existence of mine during the period of time. A dozen years ago I switched my career to the field of private education and consulting. In my visits to New England independent schools, in my stops at those small town riverside cafes, and in my interactions with individual students and parents, I realized, strongly and consciously, what Confucius had been pursuing for his entire life, what he had wanted so badly but failed to accomplish, of his ideas what had been altered to accommodate the political reality over Chinese history, and what Confucius could bring to walk China out from its dynasty cycle and become a responsible and respected member of international community. I started to be careful with the word Confucianism when it was used by different speakers. I wrote and posted a lot but planned the best for my sixties: hopefully an overhaul of Confucius and his original thoughts. It is in such a context that I came to understand Confucius as a person. I felt his despair when he uttered that well-cited phrase “rotten wood is not craftable,” referring to a witty and naughty student who truanted and slept during the day. I could not help but burst into a grimace when he already started to, almost two thousand and five hundred years ago, elaborate on students’ concerns over following your passion verse earning a living. To me, Confucius is no longer a hazy and sacred icon anymore; rather, he is a career changer, a private educator and consultant, and a colleague and mentor. In my imagination, I have plucked those gingko fruits from his Temple at Quzhou each year; I have infused each batch of the fruits in the fine liquor and labeled them carefully. I invite Confucius over for a drink, regularly, and taste the home-made vintages of different years. Most of the time, we just sit, relish the liquor, occasionally exchange a few words, and then enjoy our silence together. If he is in the mood, the old man would again recall his last fishing trip and the big fish he lost. At that moment, Ernest Hemingway would jump in and pour himself a shot. But there are a few occasions when Confucius just sits there, staring at the dark outside blankly, fixed, wordless and motionless. In a recent get- |

together, when he turns to me, glistening on his wrinkled cheeks are drops of tears, dripping.

I feel his pains. He has been wronged too many times, and for too long! In China, practice of his true teachings has been trashed; what is left is only a cloak in his name, which could be exploited by Chinese government to label anything for any purpose, such as Confucius Institute. Yandong Liu, in the center of the first row, with faculty members at Sichuan University in 2017; behind her was 89-year-old Professor Mingjing Tu. Yandong Liu was the Vice Premier of China in charge of operations of Confucius Institutes across the world. Photo: internet.

In a 2017 site visit to Sichuan University, Yandong Liu, then a Vice Premier of China and the ultimate boss of all the Confucius Institutes across the world, largessed a photo op to a group of preeminent scientists, including two members of China’s National Academy of Engineering. In the photo, Yandong Liu and her retinue occupied the first row, sitting. In the second row, from left to right, the first was 80-year-old Professor Benhe Zhong, the fourth 89-year-old Professor Mingjing Tu, and the fifth 80-year-old Professor Jie Gao, all standing; Professor Mingjing Tu managed a shaky stand-up but could fall any time. In Confucianism, elders and teachers are held in high esteem, could someone just offer Professor Mingjing Tu a chair so he could save his dignity? The photo documented how those highly respectable elders and teachers were treated by the very person who oversaw the entire operations of Confucius Institutes. If Confucius were still alive, would he have to entertain Chinese government officials just like Professor Mingjing Tu, though “honored” with a position in the center of the second row and just behind the Vice Premier?

In this photo, all the male government officials wore a fine dress shirt but no tie, while most, if not all, male faculty members--including Professor Jie Gao--were in formal dress with a tie. (I am not sure if the third person from the left in the second row is a school administrator or a professor, but his position in the photo indicates he is an important person in the university.) I have discussed the phenomena in an earlier piece posted in 2015 (中国教育:李白危害何时了? On Chinese education, when will we see the end of Li Bai mentality?). In the U.S., politicians, statesmen and many successful people frequently remove their ties and put on sneakers to connect to average Joes, a posture to show their sensitivity to social equality. In China, wearing a blazer without a tie has precisely an opposite implication: it is a privilege reserved for elites, who are entitled to defying social codes that bind ordinary bread earners; it is a blatant and conspicuous display of power and arrogance. What a show is this photo! Is this the message that the very boss of all the Confucius Institutes would like to convey to interpret the “neo-neo-neo…-Confucianism?” To those who have been “prejudiced” with the stereotypic images of Chinese government officials, this photo doesn’t surprise at all. What saddens and perplexes many, those who were once Chinese but have lived in the U.S. for decades, is the loss of decency and civility even among some who are supposed to be the role models of Chinese society and who were once our friends, colleagues, or mentors. It is always a pain to examine such a reality, it is offensive and rude to identify a specific individual in such a context, but it is significant if something could be learned from such bluntness. Lenovo founder Liu Chuanzhi is a savvy Chinese businessman for whom I have great admiration. When I see his name on a headline, I click. As a person who had suffered dearly in the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Liu is an advocate for rule of law and social responsibility. As a successful businessman in China, he is a person of insight and sophistication. I found some of his comments, though apparently casual and soft, quite enlightening and worth serious pondering. However I became stunned by one of his public talks early this year. In a China Entrepreneurs Forum in February, Liu complained about his experience at Mayo Clinic, pitying Americans for falling behind in adopting and applying new technologies. According to him, he had gone to there for medical services. He wanted to set up a chat group on Webchat to facilitate communication between his Mayo physicians and his entourage, on his medical condition and treatment. But he had only been told that people at Mayo Clinic did not use Webchat. A hospital like Mayo Clinic could definitely be trusted to have a well-established mechanism for efficient and effective communication between patients and physicians. What had made Liu feel that he needed an instant channel of communication specific for him? Would Liu feel comfortable if his doctor, when seeing him or studying his case, had to pick up the cell phone to answer a voice message, to please the family or assistant of one of his/her other 1000 patients? Confucius said, “Do not do to others what you would not have them do to you.” (The Analects of Confucius 12.2) What is more disturbing, however, is that Liu had never seemed to come to an understanding that it was the humanity, not the technology, that held Mayo physicians to skillfully decline his advance. It is weird that none of Liu’s staff had ever felt the need to respect a different culture in a different country and to save Liu from any further embarrassment. It is incredible that some Chinese media even tried to spin something out of this, out of proportion. Something is terribly wrong with China as a whole of society! Enough name calling. How about something big and current, something on the heated contention between China and the US, say, intellectual property? What would Confucius and his followers say about that? The Analects of Confucius recorded a conversation between Confucius and one of his favorite disciples Zi Gong (a.k.a. Duanmu Ci or Tzu-kung), a successful merchant as well as a shrewd politician who is worshiped as the father of commerce in traditional Chinese culture:

Gone the words and teachings from Confucius and his disciples, “like the river going down there, sparing no day or night!” (The Analects of Confucius 9.17) Confucius and Confucianism is just one of those many great things that, once of interest to China (CCP), would be fully exploited, maximally twisted, and, in the end, fundamentally ruined. Another illustration is the United Nations Human Rights Council, from which the US had to withdraw in June. An ongoing target is America’s rule of law, which has already become a cheap joke to many wealthy Chinese. While Confucianism is touted only as an ideology on paper in the real world of current China or tailored as a cloak for Chinese government to flex its influence worldwide, many of what it has been promoting are the daily practices in America. As a set of social values that aim at community harmony and long-term social well-being, Confucianism aligns well with American values. Many Chinese, with Confucianism imprinted on them, find America a great place to breathe and a desired society to integrate into. And many Chinese-Americans have honored those shared values on this land; one of them is a 15-year-old boy in Florida. Peter Wang in his JROTC uniform. Photo:internet.

Peter Wang was a student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School; he was also a cadet in the US Army Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps. On February 14, 2018, a gunman walked into his school and started a shooting rampage. Peter, in his JROTC uniform, was killed when he held the door open for his classmates to escape. Across the street from his high school was a Chinese restaurant owned by his family. His parents immigrated to America from China and did not speak English. But they presented a son that exemplifies the highest standard of two core virtues of Confucianism: “Ren” and “Yi,” or sacrifice and honor.

If Confucius were still alive, he would immigrate to America as well, and he would find himself cordially received in the U.S. His thoughts are not parochial codes patented to China. Rather they are the crystallization of human civilizations and many of them are the very existence of the everyday American life. My questions for those from Confucius Institute always are: Do they really understand Confucius and Confucianism? Have they ever practiced Confucianism? Would they like to take an internship in the U.S. on Confucianism? Maybe it is time for Chinese to come to America to learn Confucius and Confucianism, of authentic taste and original flavor. And I, for one, would be happy to offer them an entry level course in Boston: A Comparative Perspective of Confucius and His teachings 101. And I would also like to bring Confucius to Boston and file an immigration petition on his behalf. Would U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services please honor my sponsorship? |